OLED Dimming Confusion – APL, ABL, ASBL, TPC and GSR Explained

Introduction

If you’ve ever considered buying an OLED display the benefits of OLED should be well known by now – near instant response times, true blacks, basically infinite contrast ratio, per pixel dimming for HDR and generally excellent image quality. Lots of people are buying OLED TV’s and now we’re starting to see more viable options in the desktop monitor space as well with screens like the 34” ultrawide Dell Alienware AW3423DW we reviewed recently, and LG’s smallest OLED TV, the 42C2 from this year that we also reviewed recently. If you’ve looked in to these options you will probably also have read people talking about things like image retention, burn in and some of the dimming technologies that people experience with this panel technology. There’s a lot of confusing acronyms thrown around, and it’s not really very easy to understand what these technologies are, whether they are an issue, or whether these are things you might want to turn off, or even if you can!

This article will help you understand them all, so you will hopefully know your APL from your ABL, your ASBL from your TPC and everything in between.

APL = Average Picture Level

Before we talk about the OLED panel light output controls and dimming technologies, we need to understand about APL. APL (Average Picture Level) defines in simple terms how much of the image you’re displaying is bright, and how much of it is dark. A simple measurement approach you will see in reviews of OLED displays is when the brightness of different sized white windows as measured against a black background. When the white box is a quarter of the size of the overall image this simulates a 25% APL. Half the screen would be 50% APL, and a full white screen would be 100% APL. And so on. Smaller sized windows like 1% and 5% APL simulate small highlights areas as well.

The APL is important on OLED screens when considering two factors that will dictate how bright the screen can get in different situations, and that lead to screen dimming or changes in brightness levels you might experience. Unfortunately these two technologies and terms that we’re about to talk about have become very confused in the market.

ABL = Auto Brightness Limiter

This term has become a little mixed up in the OLED market and it is often used to describe two different things. The first and correct definition is related to how OLED panels operate from a technical and physics point of view. The other occasion it is often used is when talking about an image retention feature actually called ASBL or TPC, which is discussed later.

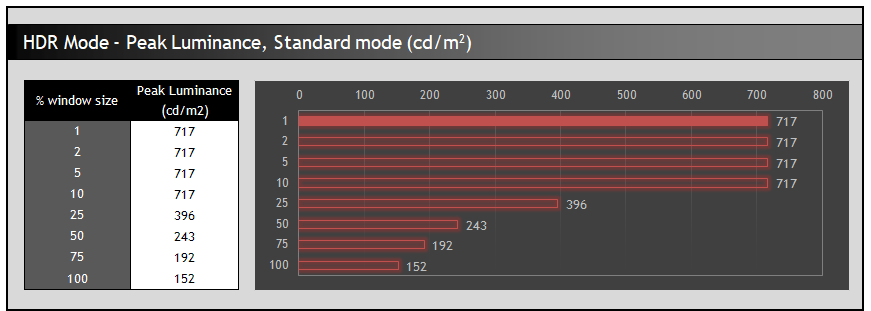

Talking about the real ABL for now, OLED panels all have an inherent limitation with the panel itself. The power consumption of these panels is highly dependent upon the content displayed. With a pure white image, every pixel must be lit, while with a pure black image every pixel is off. As the display has a maximum power usage, this opens up the capability for OLED displays to allocate more power per pixel to create a higher maximum luminance when not displaying a full-white image. This is different to LCD panels where a separate backlight unit sits behind the panel and can produce the same max luminance level regardless of the screen content (the APL), and how much of it is white and how much of it is black in this example. On the OLED screen the percentage of the display that is lit up compared with a full white display is known as the Average Picture level (APL) as we’ve talked about above. You will see then on OLED panels that with a low APL (like a small 1% or 5% window size of white) the maximum peak brightness is usually achieved. This peak brightness then reduces normally as the window size increases, as this is where the Auto Brightness Limiter (ABL) feature comes in. If you try and display a bright area over a certain window size you will find that the screen is dimmer than if that window size was smaller.

There will be a maximum brightness that the screen can reach and sustain for a pure white image (100% APL), but then if you reduce that APL you’re able to re-allocate power to only the brighter areas and therefore drive up the peak brightness in those situations. The point at which this ABL feature kicks in based on the size of the APL will vary on different panels. So this ABL feature is really a feature of how OLED panels operate, it’s not to do with image retention (although there is also a heat dissipation consideration) it’s a technical and power limitation.

Above we have included the brightness levels for the LG 42C2 as an example in its Standard HDR preset mode, at different APL/ Window sizes. You can see that for APL with a 1, 2, 5 and 10% white window size the same 717 nits peak brightness is achieved. The ABL kicks in once the APL reaches 25% or more though and reduces the luminance of the white area. Each time the APL increases, the peak brightness is reduced a bit until at 100% APL (full white screen) the screen can reach only 152 nits. The 100% APL brightness will be important to consider in a moment for SDR and desktop usage using this screen as an example. This is fairly typical behaviour for an OLED panel.

Another example is included above from the recently tested Dell Alienware AW3423DW QD-OLED monitor. You can see that the maximum peak luminance is pushed further for the 1 and 2% sized windows, resulting in a 950 – 1000 nits brightness peak. As the APL increases and as the white window gets larger, the ABL feature kicks in and the brightness is reduced. In this example on this particular screen the 100% APL brightness is 258 nits which is higher than the LG 42C2 shown above. The figures may vary from one screen to another, but the overall principle of the panel using and needing ABL remain the same.

Is ABL needed for SDR content?

ABL is generally only a factor for HDR content, where the true peak brightness of the panel can be realised. For SDR content the reference luminance is actually only 100 nits. Thinking back to the LG 42C2 example above, we know that the screen can produce 152 nits at 100% APL (full white screen) and so if you’re using the screen at 100 nits for SDR, the ABL will actually never need to kick in. The same brightness max of 100 nits can be realised at any APL comfortably.

Obviously some people might want to run their screens a bit brighter than the SDR reference 100 nits, but even 150 nits is fine without needing APL. This is the luminance level I personally use for the LG OLED TV by the way in my typical viewing conditions. If you wanted it a bit brighter at say 200 nits for a bright viewing environment then the screen can pretty much handle that at APL’s up to 75%, and only if you have a full 100% APL would it need to dim the screen a little. So for SDR use for most people, ABL is unlikely to ever be a factor.

Keep in mind this could vary from one screen to another, but a good thing to check in reviews would be the brightness capability at 100% APL. I’d be surprised if any OLED couldn’t cover 100 nits though easily at 100% APL.

Is ABL needed for desktop monitor use?

If we think then about desktop monitor usage, the recommended luminance level for a monitor in normal lighting conditions would be 120 nits. Again that’s easily achieved on the LG 42C2 with even 100% APL. The same considerations apply if you wanted a brighter screen as when talking about SDR, but again for most people ABL shouldn’t be a factor for desktop monitor on OLED screens.

When ABL is needed, is it obvious?

HDR is the most common situation where ABL would be needed. You’re pretty much going to want the screen to reach as bright as it can for HDR content with today’s OLED screens and so the ability to boost brightness for smaller areas (low APL) is a useful thing. Unlike LCD panels though where a backlight is used, you won’t get the same peak brightness at all APL’s for the reasons explained above.

Where ABL is used in HDR situations, older OLED panels tended to be poorer at handling the changes and you could sometimes see noticeable dimming and brightness changes as scenes changed. This was often with a short lag as well, so even in real usage and dynamic content sometimes things appeared to be dimming and brightening oddly. This was simply the screen adjusting because of the ABL. On modern OLED panels it is much less of an issue and generally the algorithms that control this do so very well. Personally I have very rarely seen issues with this in normal usage on OLED TV’s I’ve used. Some people do find it problematic or distracting, and sometimes will rule out OLED as a result. If you want super high peak brightness beyond what you can get from OLED today, and the ability to keep that same peak brightness at all APL’s then an LCD panel with something like a Mini LED backlight might be a better solution for you.

Can you disable ABL?

There is no way to disable ABL at all, even using a service menu of an OLED screen – it’s an inherent technical and power limitation. Nothing you can change in any service menu would turn this off.

ASBL = Auto Static Brightness Limiter,

also known as TPC = Temporal Peak Luminance Control

What makes this a bit confusing is that in the OLED TV space the term “ABL” has become associated often with something different, a specific image retention feature seen on OLED TV’s that also dims or “limits” the brightness. Sometimes called “Auto Static Brightness Limiter” (ASBL), this is what LG who are one of the leading OLED TV manufacturers call “Temporal Peak Luminance Control” (TPC). Because it dims the screen it’s become associated with the term ABL as well confusingly, even though it’s not actually ABL at all.

This image retention saving feature detects static content on the screen and unless there is a regular (but fairly small) change in the APL the pixels are dimmed in brightness to help try and avoid image retention problems. In the most common usage for a TV of video, movies, gaming etc the content and therefore the APL is changing regularly and so you should rarely see this TPC feature kick in, although if you leave something paused for a short while you should notice it. That’s what TPC is designed for, when the TV thinks you’ve left it paused it will reduce the brightness a bit to try and help reduce image retention risk. Of course it doesn’t eliminate the risk, as you’re still leaving an OLED screen with static content on it which is generally not advisable, but it might help a bit. That’s the theory anyway.

The problem comes when some users might spot TPC kicking in during dynamic scenes where there are minimal changes to the APL, most commonly on extended darker scenes in movies or games. In those instances the TV is being overly aggressive with the TPC feature, not realising that actually it’s dynamic content and is not static, and is then dimming the screen unnecessarily. This makes an already dark scene even darker which can be hard to see. Arguably in darker scenes the pixel light is already very low anyway relative to your typical brightness levels, so it’s overkill to dim this even further for the sake of image retention mitigation.

With TPC dimming, when the APL changes again the screen brightness increases back to what it was before which can be jarring if it’s kicked in during a dark scene or dynamic content when perhaps it shouldn’t have. On LG TV’s the TPC feature kicks in quite quickly after only a short amount of time with what the screen feels is a static image, or an insufficient change in the APL at least.

TPC concerns for desktop monitor use

If you’re using the screen for desktop PC usage then working with static content can result in this feature turning on quite easily, and you will spot the overall image dim after a couple of minutes. Having tested and reviewed both the LG CX and LG C2 OLED TV’s as a PC monitor this is fairly noticeable in those uses. Desktop use is probably the main area where you’d see this TPC feature kick in. On the other hand there are OLED displays which are specifically desktop monitors like the LG UltraFine 32EP950 Pro and the Dell Alienware AW3423DW that we’ve tested which do not have this kind of TPC/ASBL feature at all.

Even if the screen does have it, like the OLED TV’s then you need to remember though that it doesn’t change the fact the image is still largely static for desktop use with limited changes to the APL. All TPC is really doing is reducing the brightness of the OLED pixels in an effort to try and reduce the chance of burn in. The brighter the pixels are operating, the more likely burn in could occur. So the logic being is it will reduce the brightness a bit to try and help.

GSR = Global Sticky Reduction

Another acronym to throw in to the mix is GSR, or ‘Global Sticky Reduction’. This is a feature designed to detects smaller parts of a static image and dim those areas a bit. This is the technology behind the logo protection features you might see in the OSD menu for some OLED TV’s, including the popular LG models. Generally this is harder to see in real use as it’s only dimming a small area of the screen, but it could be more problematic for desktop monitor use. There are usually options in the OSD menu to control how strong this feature is, and also turn it off – although it may not fully turn it off even with that setting it seems based on additional service menu options discussed below.

Disabling ASBL, TPC and GSR

You can disable ASBL/TPC and GSR from the service menu on LG TV’s, do so at your own risk

Disclaimer: We should start by saying that we cannot recommend or condone accessing a display’s service menu or changing settings in there. Any access or setting changes are done entirely at your own risk and we cannot be held accountable for any issues you might face. We are including discussion of this topic here for completeness and interest. There’s plenty of discussion about this online, we don’t want to pretend this isn’t an option some people like to take, but please consider your own personal use case and any risks appropriately.

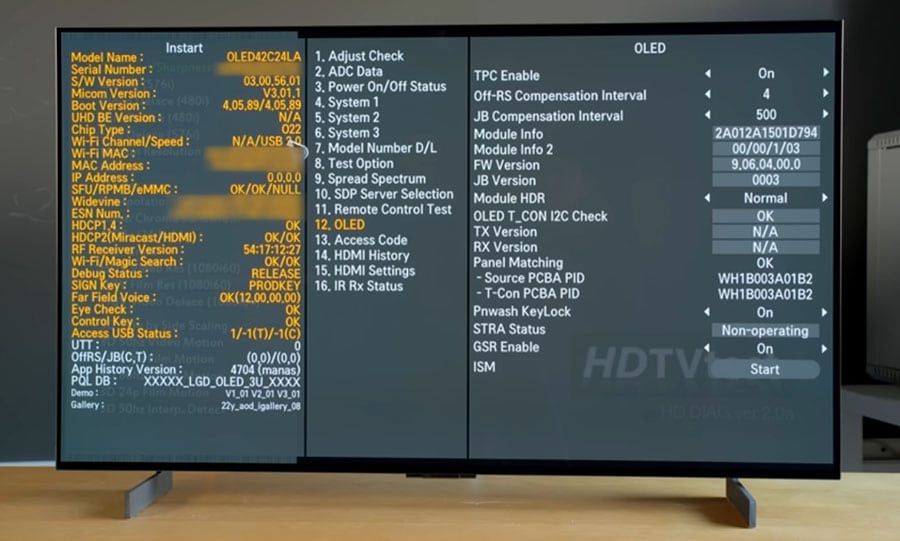

How to access the service menu on an LG OLED TV

Like we said above, we can’t recommend or condone this but we don’t want to pretend like this doesn’t exist. Many LG OLED TV owners use this approach and we include it here for completeness and reference. You’ll only go off and find it elsewhere anyway if this is something you want to explore and choose to ignore our warnings.

You cannot access the TV service menu (at least on modern LG OLED TV’s) with the normal provided remote. You would need some kind of service remote, but these are low cost at around £10 / $10 from Amazon (affiliate link). You can access the service menu using the “in-start” button on these remotes as it’s usually labelled, and the access code for the menu on LG OLED TV’s is usually 0413.

Once in the service menu we would strongly advise against changing anything else, but the two settings discussed in this article are located in the ‘OLED’. You can see the TPC and GSR options shown in the screenshot above, courtesy of HDTVTest’s LG C2 vs Dell Alienware AW3423DW comparison video.

TPC, also known as ASBL can be turned off, as can GSR if you want to from here.

Disabling TPC for TV usage is likely low risk

If you’re using the screen primarily as a TV for actual dynamic content with moving image like a TV show, movie, game etc it is really unnecessary for TPC to kick in, and it’s not really meant to do so either. It’s kicking in when it probably really shouldn’t. So for TV usage, that’s when some people want to turn it off via the service menu to avoid that distraction.

That’s a very valid reason to do so in our opinion, and the only “risk” in that is if you are in the habit of leaving the screen paused or static, it will no longer activate TPC and try and help you a bit. For the actual dynamic content it should have absolutely no risk, as it’s just stopping something from activating that shouldn’t be activating anyway. If you do disable it you might want to be a little extra careful to not leave it paused or on static screens, but as we said earlier it’s still a static image either way – it’s just a slightly darker static image with TPC enabled and therefore a bit less risky.

Disabling TPC for PC usage may add some risk, but it’s debatable

For PC usage it’s a little different and probably more annoying as a feature and likely to be experienced in real use. TPC will activate when there’s limited APL changes, dropping you from your normal brightness down to a lower level, again to try and help reduce the risk of burn in. But you could achieve the same thing in effect if you just operated the screen at a lower OLED light level (brightness) to start with. TPC will still kick in and dim you even further, but it’s not really needed then.

For example (some approx. numbers here) if you ran the screen at 100% OLED light level that was operating at 250 nits, when the screen detects static content and an unchanging APL, it might dim you to the equivalent of say 75% OLED light and 180 nits. You could of course instead just run the screen at 75% OLED light level all the time and disable TPC and that would be the equivalent of you always operating in the “safer” mode, if you see what we mean? That would be better than the TPC-enabled mode anyway.

If you want to consider turning TPC off in the service menu, the trick would be to find an OLED light level that is comfortable and appropriate for your static desktop use, and that has a lower chance of burn in. Using the LG 42C2 as an example we expect for most people a setting around 38% OLED light giving you a 120 nits approx. luminance would be appropriate and comfortable. This would probably be considered a “low” OLED light level in the grand scheme of things when operating an OLED screen that can handle peak brightness up to ~720 nits, and therefore a safer, less-likely-to-cause-burn-in brightness level. Remember that TPC is a safety measure, it has no real link to the actual brightness setting, it just dims the screen when it thinks the content is static with an unchanging APL. If you’re operating the screen at a lower OLED light level like that, it’s of a smaller risk to disable TPC than it would be if you were using the screen at say 100% OLED light level all the time.

The alternative default approach with TPC enabled we expect is that most people end up for PC usage setting the screen brighter than they would normally want it, putting up with that for a few minutes, then letting TPC lower you to your comfortable level. That is of course pointless and “worse” from an image retention point of view than just leaving it at the lower level all the time. Why mess around with it when you can just set yourself at the correct, comfortable level from the outset?

We don’t see there being any major risk in turning TPC off for PC use as long as you’re not going to be running at a really bright OLED light level all the time and then leaving the screen really static. There is far more benefit to be had from a burn-in mitigation point of view in being careful with your content, moving things around, hiding task bars, using screensavers etc than there is in letting a feature like TPC dim you a bit sometimes when it feels like it! And if you’re using the screen primarily for its intended usage like gaming, movies, HDR and only a bit for office /static work, it’s a really small concern anyway. If you’re mainly using it for static/office work, you’ve probably brought the wrong screen/panel tech to start with! Again, disable this at your own risk, but we would argue it’s a low risk if you’re sensible.

One other thing to consider is that OLED panels that are specifically designed for monitor use generally leave these ASBL / TPC features off altogether. It wasn’t included on the LG 32EP950 OLED professional monitor, or the Dell Alienware AW3423DW gaming monitor. That’s because the manufacturers know that it’s an annoying feature for desktop type use. To try and avoid risks with burn in they instead limit the maximum SDR brightness a bit usually or provide more frequent pixel “cleaning” and refresh features. In the case of the Dell AW3423DW it could reach around 250 nits in desktop use, but again you’re far more likely to be running it lower than that. LG have announced a monitor-version of their 48″ OLED screens recently too with the 48GQ900 pictured above. It isn’t confirmed but we would be very surprised if this features a TPC feature. It seems to again have a low SDR brightness of 135 nits. So if you do buy an LG OLED TV, running that at a sensible and comfortable luminance should be absolutely fine – well, LG think it’s fine (in all likelihood) for their monitor version.

Does this void your warranty?

If you contact LG and ask about this, they will of course tell you that accessing the service menu voids your warranty. That should be obvious and as we said earlier, any changes you might make are entirely at your own risk. However, we should think about this a little further to consider the scenarios where this might come in to effect. What people are most concerned about is voiding their warranty if they had a burn-in problem, or for LG to somehow know they’ve done this “terribly naughty” thing if the screen needs repairing for something else unrelated. The question is, would this ever matter for a warranty claim anyway? And, would anyone even know if you had accessed the service menu?

LG (in the UK at least) provide a 12 month standard warranty for the TV as detailed here: https://www.lg.com/uk/support/warranty for the CX, C1 and C2 OLED displays (those being the models considered here for possible monitor usage at 48″ and 42″ sizes). That 1 year warranty covers all TV parts including the panel, and while it’s not specifically talked about on their webpage, reports from media outlets such as the Verge suggest that LG will cover image retention within their warranty as long as it’s been used in “normal viewing conditions”. That’s open to interpretation but we suspect as long as you’re not using it for something weird (and quite famously) like a flight arrivals board at an airport with constant static images, it would be “normal”.

For the C models after that 12 months you do not have any cover from LG. Their flagship Z1 and G1 OLED TV’s have a 5 yr panel warranty though (again, at least in the UK). Warranty periods may vary by region, check your local LG website for more information.

So that means for the first 12 month period if you did have an image retention problem you could in theory claim this under LG’s warranty. If you’ve caused that through careless usage after disabling protection features then next thing you need to consider is whether LG would even know you’d done this? Could you just go back in to the menu and turn it back on? Obviously this is deliberately misleading and fraudulent, and again we cannot recommend this. We are simply discussing the situation to provoke thought. There’s scaremongering online about how LG would somehow know you’ve accessed the service menu. It’s certainly not recorded in the service menu anywhere that you’ve been in there and unless there’s some extra level 2 service menu (doubtful given this is a service menu anyway) or some kind of logging function (again doubtful they’d build that in), it’s unlikely anyone would ever know.

Would an engineer even check?

Anyway, officially yes, disabling things like TPC and GSR will void your warranty, so for the millionth time, do so at your own risk! 🙂

So after that 12 month period you could then consider additional warranties provided by retailers such as John Lewis (5 yr) or Richer Sounds (6 yr) in the UK, but they will not replace it for burn in or image retention anyway it seems. John Lewis’ web-page on this topic for instance says: “YOUR GUARANTEE WON’T COVER: “Image ghosting or screen burn. These can appear on a screen that’s left operating for a prolonged period with either a still image or a channel constantly displaying a logo”. Richer Sounds also say on their warranty page: “Exceptions: Screen burn caused by channel logos or other static images.”

So that means for these two main retailers in the UK, you’d never be in a position to be claiming for a burn in problem. You always have to be careful with OLED screens when using them for static images, and as we’ve discussed above it is debatable whether or not disabling these TPC and GSR dimming features makes that any more risky in real situations. It will be a judgement call based on your usage as to whether you want to consider disabling them, or whether you find them annoying in the first place.

Considering then that those retailers who offer the >12 month warranty period don’t cover burn-in anyway, what about if you develop another different fault after that period and have to claim under the warranty? Would they honour it if you’d accessed the service menu? We doubt very much they would even check that kind of thing, they likely don’t have the expertise or means – and why would they bother if for instance the power supply broke, or the cables got damaged or something like that? Why would it even matter if you had changed it, when the warranty claim is not for image retention issues anyway?

Accessing or changing anything in a hidden service menu should of course not be taken lightly and each person should consider their own usage, risks etc but we don’t believe that from a warranty point of view it needs to be a huge deciding factor to be honest. That’s just our take on it, you are of course welcome to your own opinions on the matter.

Conclusion

Hopefully this article has helped explain what all these acronyms actually mean, and the situations in which you might see brightness dimming on an OLED panel. As a quick TL;DR for those who skipped straight to the conclusion – APL is about how much of the screen is dark or bright at any given time and has a direct impact on the dimming technologies on OLED. ABL, perhaps the most commonly misunderstood and mislabelled technical feature, is all about directing the power supply of the screen to the panel and providing the highest brightness possible for smaller highlight areas, but at the same time means that you will experience dimming of those areas as more of the screen becomes bright. That’s unavoidable and cannot be disabled, but its relevance and impact will vary from one screen to another, and certainly based on your usage for SDR, desktop, HDR etc.

Then we talked about image retention measures like ASBL, also known by LG as TPC which dim the brightness when a static image is detected. What they are designed for, whether or not they will be seen in real use, their annoyance for desktop monitor usage and how/if you might want to consider disabling them. The same goes for GSR as an additional local panel “logo” dimming feature.

We may earn a commission if you purchase from our affiliate links in this article- TFTCentral is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Programme, an affiliate advertising programme designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.ca and other Amazon stores worldwide. We also participate in a similar scheme for Overclockers.co.uk, Newegg, Bestbuy , B&H and some manufacturers.

Stay Up To Date

|  |  |  |

| Browser Alerts | Follow on X | Subscribe on YouTube | Support Us |

Popular Trending Articles

Exploring the “Grey Banding” Issue Affecting Some Tandem WOLED Panels February 13, 2026 Exploring issues reported on Tandem WOLED panels with banding artefacts in certain situations, especially on dark grey colours. Is this a widespread issue to be concerned about and does it affect all OLED panels in the same way?

Exploring the “Grey Banding” Issue Affecting Some Tandem WOLED Panels February 13, 2026 Exploring issues reported on Tandem WOLED panels with banding artefacts in certain situations, especially on dark grey colours. Is this a widespread issue to be concerned about and does it affect all OLED panels in the same way? Does OLED Have a Black Crush Problem? Understanding and Testing OLED Shadow Detail February 10, 2026 Exploring black crush and shadow detail on OLED panels. Is this a problem? What causes it? Why are WOLED panels different to QD-OLED? We’ll also introduce our new testing approach.

Does OLED Have a Black Crush Problem? Understanding and Testing OLED Shadow Detail February 10, 2026 Exploring black crush and shadow detail on OLED panels. Is this a problem? What causes it? Why are WOLED panels different to QD-OLED? We’ll also introduce our new testing approach. Here’s Why You Should Only Enable HDR Mode on Your PC When You Are Viewing HDR Content May 31, 2023 Looking at a common area of confusion and the problems with SDR, desktop and normal content when running in HDR mode all the time

Here’s Why You Should Only Enable HDR Mode on Your PC When You Are Viewing HDR Content May 31, 2023 Looking at a common area of confusion and the problems with SDR, desktop and normal content when running in HDR mode all the time More Affordable OLED Monitors Are Coming, Courtesy of Asus February 26, 2026 PC Gaming might be very expensive right now, but OLED monitors don’t need to be! Our round-up looks at 4 new ROG monitors from Asus, offering great feature sets and specs at a more affordable price

More Affordable OLED Monitors Are Coming, Courtesy of Asus February 26, 2026 PC Gaming might be very expensive right now, but OLED monitors don’t need to be! Our round-up looks at 4 new ROG monitors from Asus, offering great feature sets and specs at a more affordable price Gen 4 Samsung QD-OLED 2025 Panels and Improvements April 14, 2025 A complete look at Samsung Display’s latest QD-OLED updates and news for 2025 including new technologies, improvements and specs

Gen 4 Samsung QD-OLED 2025 Panels and Improvements April 14, 2025 A complete look at Samsung Display’s latest QD-OLED updates and news for 2025 including new technologies, improvements and specs